Just before the pandemic, I had the pleasure of creating an installation with social justice organization Don’t Shoot Portland at Portland Art Museum. Titled ‘Liberated Archives’, the installation represented our artistic expression of Don’t Shoot Portlands’ ongoing Liberated Archives programming, which utilizes workshops and educational panels. The artwork is made up of archival maps depicting color lines throughout Portland with collaged photos from a decade of protests in support of families who have lost loved ones to gun violence. As residency partners during the Hank Willis Thomas exhibition, ‘All Things Being Equal’, we were invited to utilize a small area in the museum – the location we chose was directly across from Hank’s appropriation of Picassos’ Guernica, one of Picassos’ most legendary anti-war artworks. Hank’s piece, called Guernica (2016), is made up of sports jerseys to represent the literal commodification of Black men within American sports.

As fortunate as I’ve been to travel for work covering various art fairs and networking conferences, coming back to Portland was extremely eye opening for me in realizing how essential connecting creatives to opportunities and resources are. In a small city like ours I’ve seen the difficulty in gaining genuine recognition, especially as Black artists, unless they’ve been previously ‘vetted’ or deemed necessary for whatever performative action the institution or supporter deems fit. Even more unfortunate is that initial support is usually not intended to sustain the artist, but rather the supporter or institution.

My hope is that in my work I can continue to advocate for myself and others while navigating the world of social justice art by engaging in constructive and intentional dialogues and work spaces, rather than performative actions or projects that would otherwise compromise my standards.

Our annual Juneteenth programming takes the form of a week-long event series that centers children and art as part of our Childrens’ Art and Social Justice Council. Following our PAM installation, we were able to host a pop-up Freedom Lemonade store, where everything was free to youth organizers, whether those were materials to make art or resources to make their voices heard. A fine artist volunteered by hand painting these colorful ‘I Am.’ banners, based on slogans of the Civil Rights movement and Hank Willis Thomas’ ‘I Am. Amen’ series. With the children leading this March with their own art and banner projects, we celebrated Black emancipation in the streets.

When last years’ movement for Black Lives re-ignited, I was hit with a surge of trauma every time I opened my social media to see another person lost to police violence resembling a family member. Having just moved back to a city that is so in favor of white supremacy like Portland, it was hard for me to feel safe at first. When murals began appearing all over the city, it was the first time I felt an immersive art environment in Portland – the energy felt like community and trust. I’m sure there are some businesses who even wanted to have murals and probably commissioned some artists to express themselves on their storefront, but there’s also a performative facet to that. Businesses that have never shown up to support human rights began seeking these artists’ work in order to align themselves with the movement at least temporarily, mostly in a disjointed effort to protect their property.

Don’t Shoot Portland is actually an arts and education organization – so when we facilitated and negotiated the preservation of the Apple Store memorial panels, it took so many months of back and forth Zoom calls and meetings between both of our legal teams. Being part of that process in general and learning the legal intricacies and conservation techniques that came along with it was rewarding, but having to articulate the distinction between city sanctioned murals and the artistic response of so many during a civil uprising is something that can’t be undervalued.

Most of these calls weren’t easy, but they were necessary. We had to direct this process ourselves – these were not just wooden panels that could be taken down and dropped off in someones’ apartment, or placed in a park for someone to visit whenever they needed to renew their commitment to racial justice. I’m grateful to have built upon my experience in preservation and archivism through this project and to keep these stored in the meantime. Working together with the Transpak team and seeing the amount of care and consideration they placed in taking these boards down was beautiful in itself.

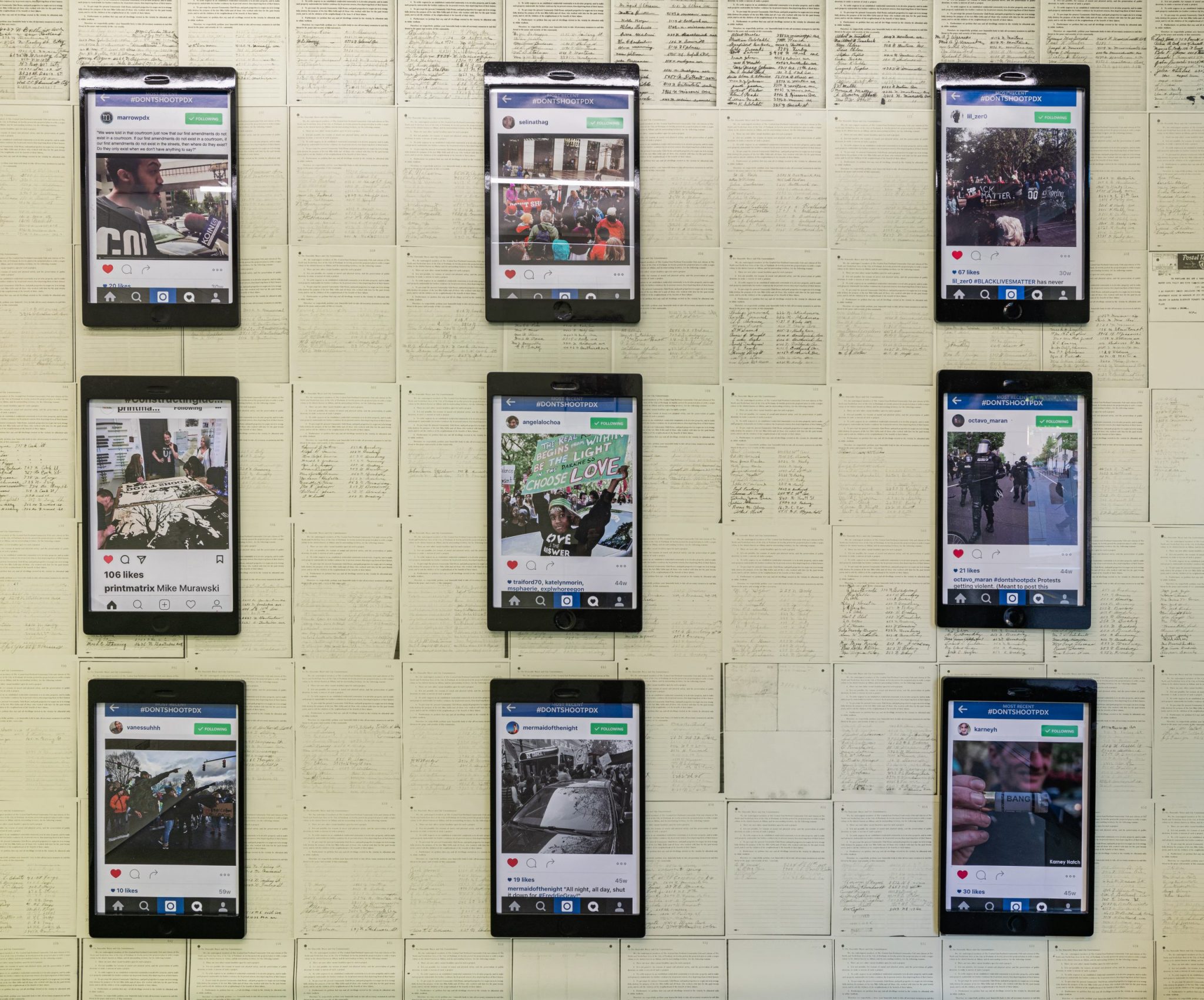

The Liberated Archives programming that we do is based in bringing historical context to the forefront in order to showcase our fight against current systems. Archivism forces you to recognize and reckon with how systemic racism and discrimination truly is. We hold an annual showing at HOLDING Contemporary, and 2021’s installation was Archives for Black Lives: A Liberated Archives exhibition. We created a vinyl wallpaper out of a 192 paged petition filed to Portland city commissioners in 1940 demanding the refusal of a Black settlement in the Albina neighborhood. The wallpaper also contained Portland council meeting minutes, City Club reports and sensationalized, racist headlines from prominent Oregon papers at the time. I think showcasing these types of documents clearly demonstrates the oppressive foundation of American policy when it comes to the populations’ it considers disposable. History can show us exactly how we arrived at our current systems of redlining, mass surveillance and the overpolicing and criminalization of Black and Brown families. I hope that with Don’t Shoot Portland, we can continue to use our programming and community action plan at large to push forward social change while elevating honest discussions about racism, activism and art in America.